Introduction

This is of interest as an early and very "pure" example of the "invasion from outer space" story, much closer in several ways to our current concept of such a situation than H. G. Wells' War of the Worlds (1898). This is in part of course because the technology of 1931 was in key respects closer to that of 2011 than that of 1898, but it is also because many of the tropes that we think of when we think of "aliens attack!" may have had their birth in this tale. You'll notice them, and you'll also probably notice the influences from WotW, which was then as recent a novel as is, say, Titan or Lucifer's Hammer today. You'll also probably notice a few technological speculations that were interestingly accurate, though in very different semantic guise from their modern usages.

I will follow this up in another post, with an analysis of the story. But I'd love comments on this by any and all in the meanwhile.

The version shown is from Project Gutenberg's Astounding collection, specifically http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/28617

(Jordan S. Bassior, (c) 2011)

Spawn of the Stars

The sky was alive with winged shapes, and high in the air shone the glittering menace, trailing five plumes of gas.

When Cyrus R. Thurston bought himself a single-motored Stoughton job he was looking for new thrills. Flying around the east coast had lost its zest: he wanted to join that jaunty group who spoke so easily of hopping off for Los Angeles.

They were roaring through the starlit, calm night, three thousand feet above a sage sprinkled desert, when the trip ended. Slim Riley had the stick when the first blast of hot oil ripped slashingly across the pilot's window. "There goes your old trip!" he yelled. "Why don't they try putting engines in these ships?"

He jammed over the throttle and, with motor idling, swept down toward the endless miles of moonlit waste. Wind? They had been boring into it. Through the opened window he spotted a likely stretch of ground.

Setting down the ship on a nice piece of Arizona desert was a mere detail for Slim.

"Let off a flare," he ordered, "when I give the word."

The white glare of it faded the stars as he sideslipped, then straightened out on his hand-picked field. The plane rolled down a clear space and stopped. The bright glare persisted while he stared curiously from the quiet cabin. Cutting the motor he opened both windows, then grabbed Thurston by the shoulder.

"'Tis a curious thing, that," he said unsteadily. His hand pointed straight ahead. The flare died, but the bright stars of the desert country still shone on a glistening, shining bulb.

It was some two hundred feet away. The lower part was lost in shadow, but its upper surfaces shone rounded and silvery like a giant bubble. It towered in the air, scores of feet above the chapparal beside it. There was a round spot of black on its side, which looked absurdly like a door....

"I saw something moving," said Thurston slowly. "On the ground I saw.... Oh, good Lord, Slim, it isn't real!"

Slim Riley made no reply. His eyes were riveted to an undulating, ghastly something that oozed and crawled in the pale light not far from the bulb. His hand was reaching, reaching.... It found what he sought; he leaned toward the window. In his hand was the Very pistol for discharging the flares. He aimed forward and up.

The second flare hung close before it settled on the sandy floor. Its blinding whiteness made the more loathsome the sickening yellow of the flabby flowing thing that writhed frantically in the glare. It was formless, shapeless, a heaving mound of nauseous matter. Yet even in its agonized writhing distortions they sensed the beating pulsations that marked it a living thing.

There were unending ripplings crossing and recrossing through the convolutions. To Thurston there was suddenly a sickening likeness: the thing was a brain from a gigantic skull—it was naked—was suffering....

The thing poured itself across the sand. Before the staring gaze of the speechless men an excrescence appeared—a thick bulb on the mass—that protruded itself into a tentacle. At the end there grew instantly a hooked hand. It reached for the black opening in the great shell, found it, and the whole loathsome shapelessness poured itself up and through the hole.

Only at the last was it still. In the dark opening the last slippery mass held quiet for endless seconds. It formed, as they watched, to a head—frightful—menacing. Eyes appeared in the head; eyes flat and round and black save for a cross slit in each; eyes that stared horribly and unchangingly into theirs. Below them a gaping mouth opened and closed.... The head melted—was gone....

And with its going came a rushing roar of sound.

From under the metallic mass shrieked a vaporous cloud. It drove at them, a swirling blast of snow and sand. Some buried memory of gas attacks woke Riley from his stupor. He slammed shut the windows an instant before the cloud struck, but not before they had seen, in the moonlight, a gleaming, gigantic, elongated bulb rise swiftly—screamingly—into the upper air.

The blast tore at their plane. And the cold in their tight compartment was like the cold of outer space. The men stared, speechless, panting. Their breath froze in that frigid room into steam clouds.

"It—it...." Thurston gasped—and slumped helpless upon the floor.

It was an hour before they dared open the door of their cabin. An hour of biting, numbing cold. Zero—on a warm summer night on the desert! Snow in the hurricane that had struck them!

"'Twas the blast from the thing," guessed the pilot; "though never did I see an engine with an exhaust like that." He was pounding himself with his arms to force up the chilled circulation.

"But the beast—the—the thing!" exclaimed Thurston. "It's monstrous; indecent! It thought—no question of that—but no body! Horrible! Just a raw, naked, thinking protoplasm!"

It was here that he flung open the door. They sniffed cautiously of the air. It was warm again—clean—save for a hint of some nauseous odor. They walked forward; Riley carried a flash.

The odor grew to a stench as they came where the great mass had lain. On the ground was a fleshy mound. There were bones showing, and horns on a skull. Riley held the light close to show the body of a steer. A body of raw bleeding meat. Half of it had been absorbed....

"The damned thing," said Riley, and paused vainly for adequate words. "The damned thing was eating.... Like a jelly-fish, it was!"

"Exactly," Thurston agreed. He pointed about. There were other heaps scattered among the low sage.

"Smothered," guessed Thurston, "with that frozen exhaust. Then the filthy thing landed and came out to eat."

"Hold the light for me," the pilot commanded. "I'm goin' to fix that busted oil line. And I'm goin' to do it right now. Maybe the creature's still hungry."

They sat in their room. About them was the luxury of a modern hotel. Cyrus Thurston stared vacantly at the breakfast he was forgetting to eat. He wiped his hands mechanically on a snowy napkin. He looked from the window. There were palm trees in the park, and autos in a ceaseless stream. And people! Sane, sober people, living in a sane world. Newsboys were shouting; the life of the city was flowing.

"Riley!" Thurston turned to the man across the table. His voice was curiously toneless, and his face haggard. "Riley, I haven't slept for three nights. Neither have you. We've got to get this thing straight. We didn't both become absolute maniacs at the same instant, but—it was not there, it was never there—not that...." He was lost in unpleasant recollections. "There are other records of hallucinations."

"Hallucinations—hell!" said Slim Riley. He was looking at a Los Angeles newspaper. He passed one hand wearily across his eyes, but his face was happier than it had been in days.

"We didn't imagine it, we aren't crazy—it's real! Would you read that now!" He passed the paper across to Thurston. The headlines were startling.

"Pilot Killed by Mysterious Airship. Silvery Bubble Hangs Over New York. Downs Army Plane in Burst of Flame. Vanishes at Terrific Speed."

"It's our little friend," said Thurston. And on his face, too, the lines were vanishing; to find this horror a reality was positive relief. "Here's the same cloud of vapor—drifted slowly across the city, the accounts says, blowing this stuff like steam from underneath. Airplanes investigated—an army plane drove into the vapor—terrific explosion—plane down in flames—others wrecked. The machine ascended with meteor speed, trailing blue flame. Come on, boy, where's that old bus? Thought I never wanted to fly a plane again. Now I don't want to do anything but."

"Where to?" Slim inquired.

"Headquarters," Thurston told him. "Washington—let's go!"

From Los Angeles to Washington is not far, as the plane flies. There was a stop or two for gasoline, but it was only a day later that they were seated in the War Office. Thurston's card had gained immediate admittance. "Got the low-down," he had written on the back of his card, "on the mystery airship."

"What you have told me is incredible," the Secretary was saying, "or would be if General Lozier here had not reported personally on the occurrence at New York. But the monster, the thing you have described.... Cy, if I didn't know you as I do I would have you locked up."

"It's true," said Thurston, simply. "It's damnable, but it's true. Now what does it mean?"

"Heaven knows," was the response. "That's where it came from—out of the heavens."

"Not what we saw," Slim Riley broke in. "That thing came straight out of Hell." And in his voice was no suggestion of levity.

"You left Los Angeles early yesterday; have you seen the papers?"

Thurston shook his head.

"They are back," said the Secretary. "Reported over London—Paris—the West Coast. Even China has seen them. Shanghai cabled an hour ago."

"Them? How many are there?"

"Nobody knows. There were five seen at one time. There are more—unless the same ones go around the world in a matter of minutes."

Thurston remembered that whirlwind of vapor and a vanishing speck in the Arizona sky. "They could," he asserted. "They're faster than anything on earth. Though what drives them ... that gas—steam—whatever it is...."

"Hydrogen," stated General Lozier. "I saw the New York show when poor Davis got his. He flew into the exhaust; it went off like a million bombs. Characteristic hydrogen flame trailed the damn thing up out of sight—a tail of blue fire."

"And cold," stated Thurston.

"Hot as a Bunsen burner," the General contradicted. "Davis' plane almost melted."

"Before it ignited," said the other. He told of the cold in their plane.

"Ha!" The General spoke explosively. "That's expansion. That's a tip on their motive power. Expansion of gas. That accounts for the cold and the vapor. Suddenly expanded it would be intensely cold. The moisture of the air would condense, freeze. But how could they carry it? Or"—he frowned for a moment, brows drawn over deep-set gray eyes—"or generate it? But that's crazy—that's impossible!"

"So is the whole matter," the Secretary reminded him. "With the information Mr. Thurston and Mr. Riley have given us, the whole affair is beyond any gage our past experience might supply. We start from the impossible, and we go—where? What is to be done?"

"With your permission, sir, a number of things shall be done. It would be interesting to see what a squadron of planes might accomplish, diving on them from above. Or anti-aircraft fire."

"No," said the Secretary of War, "not yet. They have looked us over, but they have not attacked. For the present we do not know what they are. All of us have our suspicions—thoughts of interplanetary travel—thoughts too wild for serious utterance—but we know nothing.

"Say nothing to the papers of what you have told me," he directed Thurston. "Lord knows their surmises are wild enough now. And for you, General, in the event of any hostile move, you will resist."

"Your order was anticipated, sir." The General permitted himself a slight smile. "The air force is ready."

"Of course," the Secretary of War nodded. "Meet me here to-night—nine o'clock." He included Thurston and Riley in the command. "We need to think ... to think ... and perhaps their mission is friendly."

"Friendly!" The two flyers exchanged glances as they went to the door. And each knew what the other was seeing—a viscous ocherous mass that formed into a head where eyes devilish in their hate stared coldly into theirs....

"Think, we need to think," repeated Thurston later. "A creature that is just one big hideous brain, that can think an arm into existence—think a head where it wishes! What does a thing like that think of? What beastly thoughts could that—that thing conceive?"

"If I got the sights of a Lewis gun on it," said Riley vindictively, "I'd make it think."

"And my guess is that is all you would accomplish," Thurston told him. "I am forming a few theories about our visitors. One is that it quite impossible to find a vital spot in that big homogeneous mass."

The pilot dispensed with theories: his was a more literal mind. "Where on earth did they come from, do you suppose, Mr. Thurston?"

They were walking to their hotel. Thurston raised his eyes to the summer heavens. Faint stars were beginning to twinkle; there was one that glowed steadily.

"Nowhere on earth," Thurston stated softly, "nowhere on earth."

"Maybe so," said the pilot, "maybe so. We've thought about it and talked about it ... and they've gone ahead and done it." He called to a newsboy; they took the latest editions to their room.

The papers were ablaze with speculation. There were dispatches from all corners of the earth, interviews with scientists and near scientists. The machines were a Soviet invention—they were beyond anything human—they were harmless—they would wipe out civilization—poison gas—blasts of fire like that which had enveloped the army flyer....

And through it all Thurston read an ill-concealed fear, a reflection of panic that was gripping the nation—the whole world. These great machines were sinister. Wherever they appeared came the sense of being watched, of a menace being calmly withheld. And at thought of the obscene monsters inside those spheres, Thurston's lips were compressed and his eyes hardened. He threw the papers aside.

"They are here," he said, "and that's all that we know. I hope the Secretary of War gets some good men together. And I hope someone is inspired with an answer."

"An answer is it?" said Riley. "I'm thinkin' that the answer will come, but not from these swivel-chair fighters. 'Tis the boys in the cockpits with one hand on the stick and one on the guns that will have the answer."

But Thurston shook his head. "Their speed," he said, "and the gas! Remember that cold. How much of it can they lay over a city?"

The question was unanswered, unless the quick ringing of the phone was a reply.

"War Department," said a voice. "Hold the wire." The voice of the Secretary of War came on immediately.

"Thurston?" he asked. "Come over at once on the jump, old man. Hell's popping."

The windows of the War Department Building were all alight as they approached. Cars were coming and going; men in uniform, as the Secretary had said, "on the jump." Soldiers with bayonets stopped them, then passed Thurston and his companion on. Bells were ringing from all sides. But in the Secretary's office was perfect quiet.

General Lozier was there, Thurston saw, and an imposing array of gold-braided men with a sprinkling of those in civilian clothes. One he recognized: MacGregor from the Bureau of Standards. The Secretary handed Thurston some papers.

"Radio," he explained. "They are over the Pacific coast. Hit near Vancouver; Associated Press says city destroyed. They are working down the coast. Same story—blast of hydrogen from their funnel shaped base. Colder than Greenland below them; snow fell in Seattle. No real attack since Vancouver and little damage done—" A message was laid before him.

"Portland," he said. "Five mystery ships over city. Dart repeatedly toward earth, deliver blast of gas and then retreat. Doing no damage. Apparently inviting attack. All commercial planes ordered grounded. Awaiting instructions.

"Gentlemen," said the Secretary, "I believe I speak for all present when I say that, in the absence of first hand information, we are utterly unable to arrive at any definite conclusion or make a definite plan. There is a menace in this, undeniably. Mr. Thurston and Mr. Riley have been good enough to report to me. They have seen one machine at close range. It was occupied by a monster so incredible that the report would receive no attention from me did I not know Mr. Thurston personally.

"Where have they come from? What does it mean—what is their mission? Only God knows.

"Gentlemen, I feel that I must see them. I want General Lozier to accompany me, also Doctor MacGregor, to advise me from the scientific angle. I am going to the Pacific Coast. They may not wait—that is true—but they appear to be going slowly south. I will leave to-night for San Diego. I hope to intercept them. We have strong air-forces there; the Navy Department is cooperating."

He waited for no comment. "General," he ordered, "will you kindly arrange for a plane? Take an escort or not as you think best.

"Mr. Thurston and Mr. Riley will also accompany us. We want all the authoritative data we can get. This on my return will be placed before you, gentlemen, for your consideration." He rose from his chair. "I hope they wait for us," he said.

Time was when a commander called loudly for a horse, but in this day a Secretary of War is not kept waiting for transportation. Sirening motorcycles preceded them from the city. Within an hour, motors roaring wide open, ripping into the summer night, lights slipping eastward three thousand feet below, the Secretary of War for the United States was on his way. And on either side from their plane stretched the arms of a V. Like a flight of gigantic wild geese, fast fighting planes of the Army air service bored steadily into the night, guarantors of safe convoy.

"The Air Service is ready," General Lozier had said. And Thurston and his pilot knew that from East coast to West, swift scout planes, whose idling engines could roar into action at a moment's notice, stood waiting; battle planes hidden in hangars would roll forth at the word—the Navy was cooperating—and at San Diego there were strong naval units, Army units, and Marine Corps.

"They don't know what we can do, what we have up our sleeve: they are feeling us out," said the Secretary. They had stopped more than once for gas and for wireless reports. He held a sheaf of typewritten briefs.

"Going slowly south. They have taken their time. Hours over San Francisco and the bay district. Repeating same tactics; fall with terrific speed to cushion against their blast of gas. Trying to draw us out, provoke an attack, make us show our strength. Well, we shall beat them to San Diego at this rate. We'll be there in a few hours."

The afternoon sun was dropping ahead of them when they sighted the water. "Eckener Pass," the pilot told them, "where the Graf Zeppelin came through. Wonder what these birds would think of a Zepp!

"There's the ocean," he added after a time. San Diego glistened against the bare hills. "There's North Island—the Army field." He stared intently ahead, then shouted: "And there they are! Look there!"

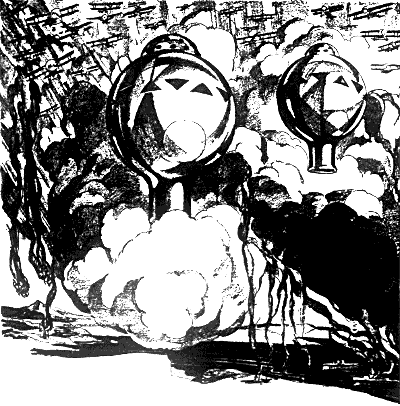

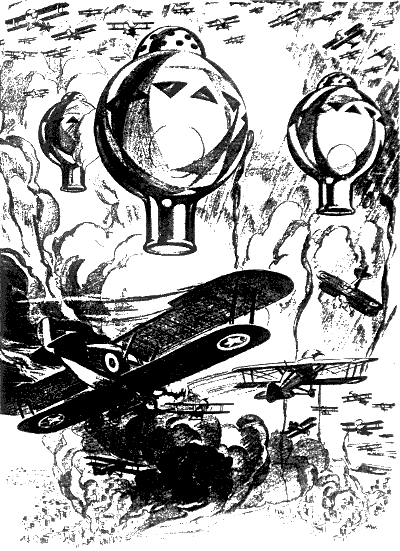

Over the city a cluster of meteors was falling. Dark underneath, their tops shone like pure silver in the sun's slanting glare. They fell toward the city, then buried themselves in a dense cloud of steam, rebounding at once to the upper air, vapor trailing behind them.

The cloud billowed slowly. It struck the hills of the city, then lifted and vanished.

"Land at once," requested the Secretary. A flash of silver countermanded the order.

It hung there before them, a great gleaming globe, keeping always its distance ahead. It was elongated at the base, Thurston observed. From that base shot the familiar blast that turned steamy a hundred feet below as it chilled the warm air. There were round orifices, like ports, ranged around the top, where an occasional jet of vapor showed this to be a method of control. Other spots shone dark and glassy. Were they windows? He hardly realized their peril, so interested was he in the strange machine ahead.

Then: "Dodge that vapor," ordered General Lozier. The plane wavered in signal to the others and swung sharply to the left. Each man knew the flaming death that was theirs if the fire of their exhaust touched that explosive mixture of hydrogen and air. The great bubble turned with them and paralleled their course.

"He's watching us," said Riley, "giving us the once over, the slimy devil. Ain't there a gun on this ship?"

The General addressed his superior. Even above the roar of the motors his voice seemed quiet, assured. "We must not land now," he said. "We can't land at North Island. It would focus their attention upon our defenses. That thing—whatever it is—is looking for a vulnerable spot. We must.... Hold on—there he goes!"

The big bulb shot upward. It slanted above them, and hovered there.

"I think he is about to attack," said the General quietly. And, to the commander of their squadron: "It's in your hands now, Captain. It's your fight."

The Captain nodded and squinted above. "He's got to throw heavier stuff than that," he remarked. A small object was falling from the cloud. It passed close to their ship.

"Half-pint size," said Cyrus Thurston, and laughed in derision. There was something ludicrous in the futility of the attack. He stuck his head from a window into the gale they created. He sheltered his eyes to try to follow the missile in its fall.

They were over the city. The criss-cross of streets made a grill-work of lines; tall buildings were dwarfed from this three thousand foot altitude. The sun slanted across a projecting promontory to make golden ripples on a blue sea and the city sparkled back in the clear air. Tiny white faces were massed in the streets, huddled in clusters where the futile black missile had vanished.

And then—then the city was gone....

A white cloud-bank billowed and mushroomed. Slowly, it seemed to the watcher—so slowly.

It was done in the fraction of a second. Yet in that brief time his eyes registered the chaotic sweep in advance of the cloud. There came a crashing of buildings in some monster whirlwind, a white cloud engulfing it all.... It was rising—was on them.

"God," thought Thurston, "why can't I move!" The plane lifted and lurched. A thunder of sound crashed against them, an intolerable force. They were crushed to the floor as the plane was hurled over and upward.

Out of the mad whirling tangle of flying bodies, Thurston glimpsed one clear picture. The face of the pilot hung battered and blood-covered before him, and over the limp body the hand of Slim Riley clutched at the switch.

"Bully boy," he said dazedly, "he's cutting the motors...." The thought ended in blackness.

There was no sound of engines or beating propellers when he came to his senses. Something lay heavy upon him. He pushed it to one side. It was the body of General Lozier.

He drew himself to his knees to look slowly about, rubbed stupidly at his eyes to quiet the whirl, then stared at the blood on his hand. It was so quiet—the motors—what was it that happened? Slim had reached for the switch....

The whirling subsided. Before him he saw Slim Riley at the controls. He got to his feet and went unsteadily forward. It was a battered face that was lifted to his.

"She was spinning," the puffed lips were muttering slowly. "I brought her out ... there's the field...." His voice was thick; he formed the words slowly, painfully. "Got to land ... can you take it? I'm—I'm—" He slumped limply in his seat.

Thurston's arms were uninjured. He dragged the pilot to the floor and got back of the wheel. The field was below them. There were planes taxiing out; he heard the roar of their motors. He tried the controls. The plane answered stiffly, but he managed to level off as the brown field approached.

Thurston never remembered that landing. He was trying to drag Riley from the battered plane when the first man got to him.

"Secretary of War?" he gasped. "In there.... Take Riley; I can walk."

"We'll get them," an officer assured him. "Knew you were coming. They sure gave you hell! But look at the city!"

Arms carried him stumbling from the field. Above the low hangars he saw smoke clouds over the bay. These and red rolling flames marked what had been an American city. Far in the heavens moved five glinting specks.

His head reeled with the thunder of engines. There were planes standing in lines and more erupting from hangars, where khaki-clad men, faces tense under leather helmets, rushed swiftly about.

"General Lozier is dead," said a voice. Thurston turned to the man. They were bringing the others. "The rest are smashed up some," the officer told him, "but I think they'll pull through."

The Secretary of War for the United States lay beside him. Men with red on their sleeves were slitting his coat. Through one good eye he squinted at Thurston. He even managed a smile.

"Well, I wanted to see them up close," he said. "They say you saved us, old man."

Thurston waved that aside. "Thank Riley—" he began, but the words ended in the roar of an exhaust. A plane darted swiftly away to shoot vertically a hundred feet in the air. Another followed and another. In a cloud of brown dust they streamed endlessly out, zooming up like angry hornets, eager to get into the fight.

"Fast little devils!" the ambulance man observed. "Here come the big boys."

A leviathan went deafeningly past. And again others came on in quick succession. Farther up the field, silvery gray planes with rudders flaunting their red, white and blue rose circling to the heights.

"That's the Navy," was the explanation. The surgeon straightened the Secretary's arm. "See them come off the big airplane carriers!"

If his remarks were part of his professional training in removing a patient's thoughts from his pain, they were effective. The Secretary stared out to sea, where two great flat-decked craft were shooting planes with the regularity of a rapid fire gun. They stood out sharply against a bank of gray fog. Cyrus Thurston forgot his bruised body, forgot his own peril—even the inferno that raged back across the bay: he was lost in the sheer thrill of the spectacle.

Above them the sky was alive with winged shapes. And from all the disorder there was order appearing. Squadron after squadron swept to battle formation. Like flights of wild ducks the true sharp-pointed Vs soared off into the sky. Far above and beyond, rows of dots marked the race of swift scouts for the upper levels. And high in the clear air shone the glittering menace trailing their five plumes of gas.

A deeper detonation was merging into the uproar. It came from the ships, Thurston knew, where anti-aircraft guns poured a rain of shells into the sky. About the invaders they bloomed into clusters of smoke balls. The globes shot a thousand feet into the air. Again the shells found them, and again they retreated.

"Look!" said Thurston. "They got one!"

He groaned as a long curving arc of speed showed that the big bulb was under control. Over the ships it paused, to balance and swing, then shot to the zenith as one of the great boats exploded in a cloud of vapor.

The following blast swept the airdrome. Planes yet on the ground went like dry autumn leaves. The hangars were flattened.

Thurston cowered in awe. They were sheltered, he saw, by a slope of the ground. No ridicule now for the bombs!

A second blast marked when the gas-cloud ignited. The billowing flames were blue. They writhed in tortured convulsions through the air. Endless explosions merged into one rumbling roar.

MacGregor had roused from his stupor; he raised to a sitting position.

"Hydrogen," he stated positively, and pointed where great volumes of flame were sent whirling aloft. "It burns as it mixes with air." The scientist was studying intently the mammoth reaction. "But the volume," he marveled, "the volume! From that small container! Impossible!"

"Impossible," the Secretary agreed, "but...." He pointed with his one good arm toward the Pacific. Two great ships of steel, blackened and battered in that fiery breath, tossed helplessly upon the pitching, heaving sea. They furnished to the scientist's exclamation the only adequate reply.

Each man stared aghast into the pallid faces of his companions. "I think we have underestimated the opposition," said the Secretary of War quietly. "Look—the fog is coming in, but it's too late to save them."

The big ships were vanishing in the oncoming fog. Whirls of vapor were eddying toward them in the flame-blaster air. Above them the watchers saw dimly the five gleaming bulbs. There were airplanes attacking: the tapping of machine-gun fire came to them faintly.

Fast planes circled and swooped toward the enemy. An armada of big planes drove in from beyond. Formations were blocking space above.... Every branch of the service was there, Thurston exulted, the army, Marine Corps, the Navy. He gripped hard at the dry ground in a paralysis of taut nerves. The battle was on, and in the balance hung the fate of the world.

The fog drove in fast. Through straining eyes he tried in vain to glimpse the drama spread above. The world grew dark and gray. He buried his face in his hands.

And again came the thunder. The men on the ground forced their gaze to the clouds, though they knew some fresh horror awaited.

The fog-clouds reflected the blue terror above. They were riven and torn. And through them black objects were falling. Some blazed as they fell. They slipped into unthought maneuvers—they darted to earth trailing yellow and black of gasoline fires. The air was filled with the dread rain of death that was spewed from the gray clouds. Gone was the roaring of motors. The air-force of the San Diego area swept in silence to the earth, whose impact alone could give kindly concealment to their flame-stricken burden.

Thurston's last control snapped. He flung himself flat to bury his face in the sheltering earth.

Only the driving necessity of work to be done saved the sanity of the survivors. The commercial broadcasting stations were demolished, a part of the fuel for the terrible furnace across the bay. But the Naval radio station was beyond on an outlying hill. The Secretary of War was in charge. An hour's work and this was again in commission to flash to the world the story of disaster. It told the world also of what lay ahead. The writing was plain. No prophet was needed to forecast the doom and destruction that awaited the earth.

Civilization was helpless. What of armies and cannon, of navies, of aircraft, when from some unreachable height these monsters within their bulbous machines could drop coldly—methodically—their diminutive bombs. And when each bomb meant shattering destruction; each explosion blasting all within a radius of miles; each followed by the blue blast of fire that melted the twisted framework of buildings and powdered the stones to make of a proud city a desolation of wreckage, black and silent beneath the cold stars. There was no crumb of comfort for the world in the terror the radio told.

Slim Riley was lying on an improvised cot when Thurston and the representative of the Bureau of Standards joined him. Four walls of a room still gave shelter in a half-wrecked building. There were candles burning: the dark was unbearable.

"Sit down," said MacGregor quietly; "we must think...."

"Think!" Thurston's voice had an hysterical note. "I can't think! I mustn't think! I'll go raving crazy...."

"Yes, think," said the scientist. "Had it occurred to you that that is our only weapon left?

"We must think, we must analyze. Have these devils a vulnerable spot? Is there any known means of attack? We do not know. We must learn. Here in this room we have all the direct information the world possesses of this menace. I have seen their machines in operation. You have seen more—you have looked at the monsters themselves. At one of them, anyway."

The man's voice was quiet, methodical. Mr. MacGregor was attacking a problem. Problems called for concentration; not hysterics. He could have poured the contents from a beaker without spilling a drop. His poise was needed: they were soon to make a laboratory experiment.

The door burst open to admit a wild-eyed figure that snatched up their candles and dashed them to the floor.

"Lights out!" he screamed at them. "There's one of 'em coming back." He was gone from the room.

The men sprang for the door, then turned to where Riley was clumsily crawling from his couch. An arm under each of his, and the three men stumbled from the room.

They looked about them in the night. The fog-banks were high, drifting in from the ocean. Beneath them the air was clear; from somewhere above a hidden moon forced a pale light through the clouds. And over the ocean, close to the water, drifted a familiar shape. Familiar in its huge sleek roundness, in its funnel-shaped base where a soft roar made vaporous clouds upon the water. Familiar, too, in the wild dread it inspired.

The watchers were spellbound. To Thurston there came a fury of impotent frenzy. It was so near! His hands trembled to tear at that door, to rip at that foul mass he knew was within.... The great bulb drifted past. It was nearing the shore. But its action! Its motion!

Gone was the swift certainty of control. The thing settled and sank, to rise weakly with a fresh blast of gas from its exhaust. It settled again, and passed waveringly on in the night.

Thurston was throbbingly alive with hope that was certainty. "It's been hit," he exulted; "it's been hit. Quick! After it, follow it!" He dashed for a car. There were some that had been salvaged from the less ruined buildings. He swung it quickly around where the others were waiting.

"Get a gun," he commanded. "Hey, you,"—to an officer who appeared—"your pistol, man, quick! We're going after it!" He caught the tossed gun and hurried the others into the car.

"Wait," MacGregor commanded. "Would you hunt elephants with a pop-gun? Or these things?"

"Yes," the other told him, "or my bare hands! Are you coming, or aren't you?"

The physicist was unmoved. "The creature you saw—you said that it writhed in a bright light—you said it seemed almost in agony. There's an idea there! Yes, I'm going with you, but keep your shirt on, and think."

He turned again to the officer. "We need lights," he explained, "bright lights. What is there? Magnesium? Lights of any kind?"

"Wait." The man rushed off into the dark.

He was back in a moment to thrust a pistol into the car. "Flares," he explained. "Here's a flashlight, if you need it." The car tore at the ground as Thurston opened it wide. He drove recklessly toward the highway that followed the shore.

The high fog had thinned to a mist. A full moon was breaking through to touch with silver the white breakers hissing on the sand. It spread its full glory on dunes and sea: one more of the countless soft nights where peace and calm beauty told of an ageless existence that made naught of the red havoc of men or of monsters. It shone on the ceaseless surf that had beaten these shores before there were men, that would thunder there still when men were no more. But to the tense crouching men in the car it shone only ahead on a distant, glittering speck. A wavering reflection marked the uncertain flight of the stricken enemy.

Thurston drove like a maniac; the road carried them straight toward their quarry. What could he do when he overtook it? He neither knew nor cared. There was only the blind fury forcing him on within reach of the thing. He cursed as the lights of the car showed a bend in the road. It was leaving the shore.

He slackened their speed to drive cautiously into the sand. It dragged at the car, but he fought through to the beach, where he hoped for firm footing. The tide was out. They tore madly along the smooth sand, breakers clutching at the flying wheels.

The strange aircraft was nearer; it was plainly over the shore, they saw. Thurston groaned as it shot high in the air in an effort to clear the cliffs ahead. But the heights were no longer a refuge. Again it settled. It struck on the cliff to rebound in a last futile leap. The great pear shape tilted, then shot end over end to crash hard on the firm sand. The lights of the car struck the wreck, and they saw the shell roll over once. A ragged break was opening—the spherical top fell slowly to one side. It was still rocking as they brought the car to a stop. Filling the lower shell, they saw dimly, was a mucouslike mass that seethed and struggled in the brilliance of their lights.

MacGregor was persisting in his theory. "Keep the lights on it!" he shouted. "It can't stand the light."

While they watched, the hideous, bubbling beast oozed over the side of the broken shell to shelter itself in the shadow beneath. And again Thurston sensed the pulse and throb of life in the monstrous mass.

He saw again in his rage the streaming rain of black airplanes; saw, too, the bodies, blackened and charred as they saw them when first they tried rescue from the crashed ships; the smoke clouds and flames from the blasted city, where people—his people, men and women and little children—had met terrible death. He sprang from the car. Yet he faltered with a revulsion that was almost a nausea. His gun was gripped in his hand as he ran toward the monster.

"Come back!" shouted MacGregor. "Come back! Have you gone mad?" He was jerking at the door of the car.

Beyond the white funnel of their lights a yellow thing was moving. It twisted and flowed with incredible speed a hundred feet back to the base of the cliff. It drew itself together in a quivering heap.

An out-thrusting rock threw a sheltering shadow; the moon was low in the west. In the blackness a phosphorescence was apparent. It rippled and rose in the dark with the pulsing beat of the jellylike mass. And through it were showing two discs. Gray at first, they formed to black, staring eyes.

Thurston had followed. His gun was raised as he neared it. Then out of the mass shot a serpentine arm. It whipped about him, soft, sticky, viscid—utterly loathsome. He screamed once when it clung to his face, then tore savagely and in silence at the encircling folds.

The gun! He ripped a blinding mass from his face and emptied the automatic in a stream of shots straight toward the eyes. And he knew as he fired that the effort was useless; to have shot at the milky surf would have been as vain.

The thing was pulling him irresistibly; he sank to his knees; it dragged him over the sand. He clutched at a rock. A vision was before him: the carcass of a steer, half absorbed and still bleeding on the sand of an Arizona desert....

To be drawn to the smothering embrace of that glutinous mass ... for that monstrous appetite.... He tore afresh at the unyielding folds, then knew MacGregor was beside him.

In the man's hand was a flashlight. The scientist risked his life on a guess. He thrust the powerful light into the clinging serpent. It was like the touch of hot iron to human flesh. The arm struggled and flailed in a paroxysm of pain.

Thurston was free. He lay gasping on the sand. But MacGregor!... He looked up to see him vanish in the clinging ooze. Another thick tentacle had been projected from the main mass to sweep like a whip about the man. It hissed as it whirled about him in the still air.

The flashlight was gone; Thurston's hand touched it in the sand. He sprang to his feet and pressed the switch. No light responded; the flashlight was out—broken.

A thick arm slashed and wrapped about him.... It beat him to the ground. The sand was moving beneath him; he was being dragged swiftly, helplessly, toward what waited in the shadow. He was smothering.... A blinding glare filled his eyes....

The flares were still burning when he dared look about. MacGregor was pulling frantically at his arm.

"Quick—quick!" he was shouting. Thurston scrambled to his feet.

One glimpse he caught of a heaving yellow mass in the white light; it twisted in horrible convulsions. They ran stumblingly—drunkenly—toward the car.

Riley was half out of the machine. He had tried to drag himself to their assistance. "I couldn't make it," he said: "then I thought of the flares."

"Thank Heaven," said MacGregor with emphasis, "it was your legs that were paralyzed, Riley, not your brain."

Thurston found his voice. "Let me have that Very pistol. If light hurts that damn thing, I am going to put a blaze of magnesium into the middle of it if I die for it."

"They're all gone," said Riley.

"Then let's get out of here. I've had enough. We can come back later on."

He got back of the wheel and slammed the door of the sedan. The moonlight was gone. The darkness was velvet just tinged with the gray that precedes the dawn. Back in the deeper blackness at the cliff-base a phosphorescent something wavered and glowed. The light rippled and flowed in all directions over the mass. Thurston felt, vaguely, its mystery—the bulk was a vast, naked brain; its quiverings were like visible thought waves....

The phosphorescence grew brighter. The thing was approaching. Thurston let in his clutch, but the scientist checked him.

"Wait," he implored, "wait! I wouldn't miss this for the world." He waved toward the east, where far distant ranges were etched in palest rose.

"We know less than nothing of these creatures, in what part of the universe they are spawned, how they live, where they live—Saturn!—Mars!—the Moon! But—we shall soon know how one dies!"

The thing was coming from the cliff. In the dim grayness it seemed less yellow, less fluid. A membrane enclosed it. It was close to the car. Was it hunger that drove it, or cold rage for these puny opponents? The hollow eyes were glaring; a thick arm formed quickly to dart out toward the car. A cloud, high above, caught the color of approaching day....

Before their eyes the vile mass pulsed visibly; it quivered and beat. Then, sensing its danger, it darted like some headless serpent for its machine.

It massed itself about the shattered top to heave convulsively. The top was lifted, carried toward the rest of the great metal egg. The sun's first rays made golden arrows through the distant peaks.

The struggling mass released its burden to stretch its vile length toward the dark caves under the cliffs. The last sheltering fog-veil parted. The thing was to the high bank when the first bright shaft of direct sunlight shot through.

Incredible in the concealment of night, the vast protoplasmic pod was doubly so in the glare of day. But it was there before them, not a hundred feet distant. And it boiled in vast tortured convulsions. The clean sunshine struck it, and the mass heaved itself into the air in a nauseous eruption, then fell limply to the earth.

The yellow membrane turned paler. Once more the staring black eyes formed to turn hopelessly toward the sheltering globe. Then the bulk flattened out on the sand. It was a jellylike mound, through which trembled endless quivering palpitations.

The sun struck hot, and before the eyes of the watching, speechless men was a sickening, horrible sight—a festering mass of corruption.

The sickening yellow was liquid. It seethed and bubbled with liberated gases; it decomposed to purplish fluid streams. A breath of wind blew in their direction. The stench from the hideous pool was overpowering, unbearable. Their heads swam in the evil breath.... Thurston ripped the gears into reverse, nor stopped until they were far away on the clean sand.

The tide was coming in when they returned. Gone was the vile putrescence. The waves were lapping at the base of the gleaming machine.

"We'll have to work fast," said MacGregor. "I must know, I must learn." He drew himself up and into the shattered shell.

It was of metal, some forty feet across, its framework a maze of latticed struts. The central part was clear. Here in a wide, shallow pan the monster had rested. Below this was tubing, intricate coils, massive, heavy and strong. MacGregor lowered himself upon it, Thurston was beside him. They went down into the dim bowels of the deadly instrument.

"Hydrogen," the physicist was stating. "Hydrogen—there's our starting point. A generator, obviously, forming the gas—from what? They couldn't compress it! They couldn't carry it or make it, not the volume that they evolved. But they did it, they did it!"

Close to the coils a dim light was glowing. It was a pin-point of radiance in the half-darkness about them. The two men bent closer.

"See," directed MacGregor, "it strikes on this mirror—bright metal and parabolic. It disperses the light, doesn't concentrate it! Ah! Here is another, and another. This one is bent—broken. They are adjustable. Hm! Micrometer accuracy for reducing the light. The last one could reflect through this slot. It's light that does it, Thurston, it's light that does it!"

"Does what?" Thurston had followed the other's analysis of the diffusion process. "The light that would finally reach that slot would be hardly perceptible."

"It's the agent," said MacGregor, "the activator—the catalyst! What does it strike upon? I must know—I must!"

The waves were splashing outside the shell. Thurston turned in a feverish search of the unexplored depths. There was a surprising simplicity, an absence of complicated mechanism. The generator, with its tremendous braces to carry its thrust to the framework itself, filled most of the space. Some of the ribs were thicker, he noticed. Solid metal, as if they might carry great weights. Resting upon them were ranged numbers of objects. They were like eggs, slender, and inches in length. On some were . They worked through the shells on long slender rods. Each was threaded finely—an adjustable arm engaged the thread. Thurston called excitedly to the other.

"Here they are," he said. "Look! Here are the shells. Here's what blew us up!"

He pointed to the slim shafts with their little propellerlike fans. "Adjustable, see? Unwind in their fall ... set 'em for any length of travel ... fires the charge in the air. That's how they wiped out our air fleet."

There were others without the propellors; they had fins to hold them nose downward. On each nose was a small rounded cap.

"Detonators of some sort," said MacGregor. "We've got to have one. We must get it out quick; the tide's coming in." He laid his hands upon one of the slim, egg-shaped things. He lifted, then strained mightily. But the object did not rise; it only rolled sluggishly.

The scientist stared at it amazed. "Specific gravity," he exclaimed, "beyond anything known! There's nothing on earth ... there is no such substance ... no form of matter...." His eyes were incredulous.

"Lots to learn," Thurston answered grimly. "We've yet to learn how to fight off the other four."

The other nodded. "Here's the secret," he said. "These shells liberate the same gas that drives the machine. Solve one and we solve both—then we learn how to combat it. But how to remove it—that is the problem. You and I can never lift this out of here."

His glance darted about. There was a small door in the metal beam. The groove in which the shells were placed led to it; it was a port for launching the projectiles. He moved it, opened it. A dash of spray struck him in the face. He glanced inquiringly at his companion.

"Dare we do it?" he asked. "Slide one of them out?"

Each man looked long into the eyes of the other. Was this, then, the end of their terrible night? One shell to be dropped—then a bursting volcano to blast them to eternity....

"The boys in the planes risked it," said Thurston quietly. "They got theirs." He stopped for a broken fragment of steel. "Try one with a fan on; it hasn't a detonator."

The men pried at the slim thing. It slid slowly toward the open port. One heave and it balanced on the edge, then vanished abruptly. The spray was cold on their faces. They breathed heavily with the realization that they still lived.

There were days of horror that followed, horror tempered by a numbing paralysis of all emotions. There were bodies by thousands to be heaped in the pit where San Diego had stood, to be buried beneath countless tons of debris and dirt. Trains brought an army of helpers; airplanes came with doctors and nurses and the beginning of a mountain of supplies. The need was there; it must be met. Yet the whole world was waiting while it helped, waiting for the next blow to fall.

Telegraph service was improvised, and radio receivers rushed in. The news of the world was theirs once more. And it told of a terrified, waiting world. There would be no temporizing now on the part of the invaders. They had seen the airplanes swarming from the ground—they would know an airdrome next time from the air. Thurston had noted the windows in the great shell, windows of dull-colored glass which would protect the darkness of the interior, essential to life for the horrible occupant, but through which it could see. It could watch all directions at once.

The great shell had vanished from the shore. Pounding waves and the shifting sands of high tide had obliterated all trace. More than once had Thurston uttered devout thanks for the chance shell from an anti-aircraft gun that had entered the funnel beneath the machine, had bent and twisted the arrangement of mirrors that he and MacGregor had seen, and, exploding, had cracked and broken the domed roof of the bulb. They had learned little, but MacGregor was up north within reach of Los Angeles laboratories. And he had with him the slim cylinder of death. He was studying, thinking.

Telephone service had been established for official business. The whole nation-wide system, for that matter, was under military control. The Secretary of War had flown back to Washington. The whole world was on a war basis. War! And none knew where they should defend themselves, nor how.

An orderly rushed Thurston to the telephone. "You are wanted at once; Los Angeles calling."

The voice of MacGregor was cool and unhurried as Thurston listened. "Grab a plane, old man," he was saying, "and come up here on the jump."

The phrase brought a grim smile to Thurston's tired lips. "Hell's popping!" the Secretary of War had added on that evening those long ages before. Did MacGregor have something? Was a different kind of hell preparing to pop? The thoughts flashed through the listener's mind.

"I need a good deputy," MacGregor said. "You may be the whole works—may have to carry on—but I'll tell you it all later. Meet me at the Biltmore."

"In less than two hours," Thurston assured him.

A plane was at his disposal. Riley's legs were functioning again, after a fashion. They kept the appointment with minutes to spare.

"Come on," said MacGregor, "I'll talk to you in the car." The automobile whirled them out of the city to race off upon a winding highway that climbed into far hills. There was twenty miles of this; MacGregor had time for his talk.

"They've struck," he told the two men. "They were over Germany yesterday. The news was kept quiet: I got the last report a half-hour ago. They pretty well wiped out Berlin. No air-force there. France and England sent a swarm of planes, from the reports. Poor devils! No need to tell you what they got. We've seen it first hand. They headed west over the Atlantic, the four machines. Gave England a burst or two from high up, paused over New York, then went on. But they're here somewhere, we think. Now listen:

"How long was it from the time when you saw the first monster until we heard from them again?"

Thurston forced his mind back to those days that seemed so far in the past. He tried to remember.

"Feeding!" interrupted the scientist. "That's the point I am making. Four days. Remember that!

"And we knew they were down in the Argentine five days ago—that's another item kept from an hysterical public. They slaughtered some thousands of cattle; there were scores of them found where the devils—I'll borrow Riley's word—where the devils had fed. Nothing left but hide and bones.

"And—mark this—that was four days before they appeared over Berlin.

"Why? Don't ask me. Do they have to lie quiet for that period miles up there in space? God knows. Perhaps! These things seem outside the knowledge of a deity. But enough of that! Remember: four days! Let us assume that there is this four days waiting period. It will help us to time them. I'll come back to that later.

"Here is what I have been doing. We know that light is a means of attack. I believe that the detonators we saw on those bombs merely opened a seal in the shell and forced in a flash of some sort. I believe that radiant energy is what fires the blast.

"What is it that explodes? Nobody knows. We have opened the shell, working in the absolute blackness of a room a hundred feet underground. We found in it a powder—two powders, to be exact.

"They are mixed. One is finely divided, the other rather granular. Their specific gravity is enormous, beyond anything known to physical science unless it would be the hypothetical neutron masses we think are in certain stars. But this is not matter as we know matter; it is something new.

"Our theory is this: the hydrogen atom has been split, resolved into components, not of electrons and the proton centers, but held at some halfway point of decomposition. Matter composed only of neutrons would be heavy beyond belief. This fits the theory in that respect. But the point is this: When these solids are formed—they are dense—they represent in a cubic centimeter possibly a cubic mile of hydrogen gas under normal pressure. That's a guess, but it will give you the idea.

"Not compressed, you understand, but all the elements present in other than elemental form for the reconstruction of the atom ... for a million billions of atoms.

"Then the light strikes it. These dense solids become instantly a gas—miles of it held in that small space.

"There you have it: the gas, the explosion, the entire absence of heat—which is to say, its terrific cold—when it expands."

Slim Riley was looking bewildered but game. "Sure, I saw it snow," he affirmed, "so I guess the rest must be O.K. But what are we going to do about it? You say light kills 'em, and fires their bombs. But how can we let light into those big steel shells, or the little ones either?"

"Not through those thick walls," said MacGregor. "Not light. One of our anti-aircraft shells made a direct hit. That might not happen again in a million shots. But there are other forms of radiant energy that do penetrate steel...."

The car had stopped beside a grove of eucalyptus. A barren, sun-baked hillside stretched beyond. MacGregor motioned them to alight.

Riley was afire with optimism. "And do you believe it?" he asked eagerly. "Do you believe that we've got 'em licked?"

Thurston, too, looked into MacGregor's face: Riley was not the only one who needed encouragement. But the gray eyes were suddenly tired and hopeless.

"You ask what I believe," said the scientist slowly. "I believe we are witnessing the end of the world, our world of humans, their struggles, their grave hopes and happiness and aspirations...."

He was not looking at them. His gaze was far off in space.

"Men will struggle and fight with their puny weapons, but these monsters will win, and they will have their way with us. Then more of them will come. The world, I believe, is doomed...."

He straightened his shoulders. "But we can die fighting," he added, and pointed over the hill.

"Over there," he said, "in the valley beyond, is a charge of their explosive and a little apparatus of mine. I intend to fire the charge from a distance of three hundred yards. I expect to be safe, perfectly safe. But accidents happen.

"In Washington a plane is being prepared. I have given instructions through hours of phoning. They are working night and day. It will contain a huge generator for producing my ray. Nothing new! Just the product of our knowledge of radiant energy up to date. But the man who flies that plane will die—horribly. No time to experiment with protection. The rays will destroy him, though he may live a month.

"I am asking you," he told Cyrus Thurston, "to handle that plane. You may be of service to the world—you may find you are utterly powerless. You surely will die. But you know the machines and the monsters; your knowledge may be of value in an attack." He waited. The silence lasted for only a moment.

"Why, sure," said Cyrus Thurston.

He looked at the eucalyptus grove with earnest appraisal. The sun made lovely shadows among their stripped trunks: the world was a beautiful place. A lingering death, MacGregor had intimated—and horrible.... "Why, sure," he repeated steadily.

Slim Riley shoved him firmly aside to stand facing MacGregor.

"Sure, hell!" he said. "I'm your man, Mr. MacGregor.

"What do you know about flying?" he asked Cyrus Thurston. "You're good—for a beginner. But men like you two have got brains, and I'm thinkin' the world will be needin' them. Now me, all I'm good for is holdin' a shtick"—his brogue had returned to his speech, and was evidence of his earnestness.

"And, besides"—the smile faded from his lips, and his voice was suddenly soft—"them boys we saw take their last flip was just pilots to you, just a bunch of good fighters. Well, they're buddies of mine. I fought beside some of them in France.... I belong!"

He grinned happily at Thurston. "Besides," he said, "what do you know about dog-fights?"

MacGregor gripped him by the hand. "You win," he said. "Report to Washington. The Secretary of War has all the dope."

He turned to Thurston. "Now for you! Get this! The enemy machines almost attacked New York. One of them came low, then went back, and the four flashed out of sight toward the west. It is my belief that New York is next, but the devils are hungry. The beast that attacked us was ravenous, remember. They need food and lots of it. You will hear of their feeding, and you can count on four days. Keep Riley informed—that's your job.

"Not exactly encouraging," Thurston pondered, "but he's a good man, Mac, a good egg! Not as big a brain as the one we saw, but perhaps it's a better one—cleaner—and it's working!"

They were sheltered under the brow of the hill, but the blast from the valley beyond rocked them like an earthquake. They rushed to the top of the knoll. MacGregor was standing in the valley; he waved them a greeting and shouted something unintelligible.

The gas had mushroomed into a cloud of steamy vapor. From above came snowflakes to whirl in the churning mass, then fall to the ground. A wind came howling about them to beat upon the cloud. It swirled slowly back and down the valley. The figure of MacGregor vanished in its smothering embrace.

"Exit, MacGregor!" said Cyrus Thurston softly. He held tight to the struggling figure of Slim Riley.

"He couldn't live a minute in that atmosphere of hydrogen," he explained. "They can—the devils!—but not a good egg like Mac. It's our job now—yours and mine."

Slowly the gas retreated, lifted to permit their passage down the slope.

MacGregor was a good prophet. Thurston admitted that when, four days later, he stood on the roof of the Equitable Building in lower New York.

The monsters had fed as predicted. Out in Wyoming a desolate area marked the place of their meal, where a great herd of cattle lay smothered and frozen. There were ranch houses, too, in the circle of destruction, their occupants frozen stiff as the carcasses that dotted the plains. The country had stood tense for the following blow. Only Thurston had lived in certainty of a few days reprieve. And now had come the fourth day.

In Washington was Riley. Thurston had been in touch with him frequently.

"Sure, it's a crazy machine," the pilot had told him, "and 'tis not much I think of it at all. Neither bullets nor guns, just this big glass contraption and speed. She's fast, man, she's fast ... but it's little hope I have." And Thurston, remembering the scientist's words, was heartless and sick with dreadful certainty.

There were aircraft ready near New York; it was generally felt that here was the next objective. The enemy had looked it over carefully. And Washington, too, was guarded. The nation's capital must receive what little help the aircraft could afford.

There were other cities waiting for destruction. If not this time—later! The horror hung over them all.

The fourth day! And Thurston was suddenly certain of the fate of New York. He hurried to a telephone. Of the Secretary of War he implored assistance.

"Send your planes," he begged. "Here's where we will get it next. Send Riley. Let's make a last stand—win or lose."

"I'll give you a squadron," was the concession. "What difference whether they die there or here...?" The voice was that of a weary man, weary and sleepless and hopeless.

"Good-by Cy, old man!" The click of the receiver sounded in Thurston's ear. He returned to the roof for his vigil.

To wait, to stride nervously back and forth in impotent expectancy. He could leave, go out into open country, but what were a few days or months—or a year—with this horror upon them? It was the end. MacGregor was right. "Good old Mac!"

There were airplanes roaring overhead. It meant.... Thurston abruptly was cold; a chill gripped at his heart.

The paroxysm passed. He was doubled with laughter—or was it he who was laughing? He was suddenly buoyantly carefree. Who was he that it mattered? Cyrus Thurston—an ant! And their ant-hill was about to be snuffed out....

He walked over to a waiting group and clapped one man on the shoulder. "Well, how does it feel to be an ant?" he inquired and laughed loudly at the jest. "You and your millions of dollars, your acres of factories, your steamships, railroads!"

The man looked at him strangely and edged cautiously away. His eyes, like those of the others, had a dazed, stricken look. A woman was sobbing softly as she clung to her husband. From the streets far below came a quavering shrillness of sound.

The planes gathered in climbing circles. Far on the horizon were four tiny glinting specks....

Thurston stared until his eyes were stinging. He was walking in a waking sleep as he made his way to the stone coping beyond which was the street far below. He was dead—dead!—right this minute. What were a few minutes more or less? He could climb over the coping; none of the huddled, fear-gripped group would stop him. He could step out into space and fool them, the devils. They could never kill him....

He straightened slowly and drew one long breath. He looked steadily and unafraid at the advancing specks. They were larger now. He could see their round forms. The planes were less noisy: they were far up in the heights—climbing—climbing.

The bulbs came slantingly down. They were separating. Thurston wondered vaguely.

What had they done in Berlin? Yes, he remembered. Placed themselves at the four corners of a great square and wiped out the whole city in one explosion. Four bombs dropped at the same instant while they shot up to safety in the thin air. How did they communicate? Thought transference, most likely. Telepathy between those great brains, one to another. A plane was falling. It curved and swooped in a trail of flame, then fell straight toward the earth. They were fighting....

Thurston stared above. There were clusters of planes diving down from on high. Machine-guns stuttered faintly. "Machine-guns—toys! Brave, that was it! 'We can die fighting.'" His thoughts were far off; it was like listening to another's mind.

The air was filled with swelling clouds. He saw them before the blast struck where he stood. The great building shuddered at the impact. There were things falling from the clouds, wrecks of planes, blazing and shattered. Still came others; he saw them faintly through the clouds. They came in from the West; they had gone far to gain altitude. They drove down from the heights—the enemy had drifted—they were over the bay.

More clouds, and another blast thundering at the city. There were specks, Thurston saw, falling into the water.

Again the invaders came down from the heights where they had escaped their own shattering attack. There was the faint roar of motors behind, from the south. The squadron from Washington passed overhead.

They surely had seen the fate that awaited. And they drove on to the attack, to strike at an enemy that shot instantly into the sky leaving crashing destruction about the torn dead.

"Now!" said Cyrus Thurston aloud.

The big bulbs were back. They floated easily in the air, a plume of vapor billowing beneath. They were ranging to the four corners of a great square.

One plane only was left, coming in from the south, a lone straggler, late for the fray. One plane! Thurston's shoulders sagged heavily. All they had left! It went swiftly overhead.... It was fast—fast. Thurston suddenly knew. It was Riley in that plane.

"Go back, you fool!"—he was screaming at the top of his voice—"Back—back—you poor, damned, decent Irishman!"

Tears were streaming down his face. "His buddies," Riley had said. And this was Riley, driving swiftly in, alone, to avenge them....

He saw dimly as the swift plane sped over the first bulb, on and over the second. The soft roar of gas from the machines drowned the sound of his engine. The plane passed them in silence to bank sharply toward the third corner of the forming square.

He was looking them over, Thurston thought. And the damn beasts disregarded so contemptible an opponent. He could still leave. "For God's sake, Riley, beat it—escape!"

Thurston's mind was solely on the fate of the lone voyager—until the impossible was borne in upon him.

The square was disrupted. Three great bulbs were now drifting. The wind was carrying them out toward the bay. They were coming down in a long, smooth descent. The plane shot like a winged rocket at the fourth great, shining ball. To the watcher, aghast with sudden hope, it seemed barely to crawl.

"The ray! The ray...." Thurston saw as if straining eyes had pierced through the distance to see the invisible. He saw from below the swift the streaming, intangible ray. That was why Riley had flown closely past and above them—the ray poured from below. His throat was choking him, strangling....

The last enemy took alarm. Had it seen the slow sinking of its companions, failed to hear them in reply to his mental call? The shining pear shape shot violently upward; the attacking plane rolled to a vertical bank as it missed the threatening clouds of exhaust. "What do you know about dog-fights?" And Riley had grinned ... Riley belonged!

The bulb swelled before Thurston's eyes in its swift descent. It canted to one side to head off the struggling plane that could never escape, did not try to escape. The steady wings held true upon their straight course. From above came the silver meteor; it seemed striking at the very plane itself. It was almost upon it before it belched forth the cushioning blast of gas.

Through the forming clouds a plane bored in swiftly. It rolled slowly, was flying upside down. It was under the enemy! Its ray.... Thurston was thrown a score of feet away to crash helpless into the stone coping by the thunderous crash of the explosion.

There were fragments falling from a dense cloud—fragments of curved and silvery metal ... the wing of a plane danced and fluttered in the air....

"He fired its bombs," whispered Thurston in a shaking voice. "He killed the other devils where they lay—he destroyed this with its own explosive. He flew upside down to shoot up with the ray, to set off its shells...."

His mind was fumbling with the miracle of it. "Clever pilot, Riley, in a dog-fight...." And then he realized.

Cyrus Thurston, millionaire sportsman, sank slowly, numbly to the roof of the Equitable Building that still stood. And New York was still there ... and the whole world....

He sobbed weakly, brokenly. Through his dazed brain flashed a sudden, mind-saving thought. He laughed foolishly through his sobs.

"And you said he'd die horribly, Mac, a horrible death." His head dropped upon his arms, unconscious—and safe—with the rest of humanity.

.

END.

I never trusted those space amoebas. I'll be interested to read your commentary. And FYI, Project Gutenberg suggests that you link to a book's catalog page rather than directly to the ebook file.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the heads-up on the linkage ... I can see why, because someone else might not have the same browser or reader as I do. Nice to see people interested in classic science fiction! :)

ReplyDelete